|

ABSTRACT

Research was conducted on the predictors of burnout in a sample

of teachers in Queensland private schools. A total of 246 teachers

responded to scales that assessed burnout, school and classroom

environments, work pressure, role overload, role ambiguity, role

conflict, teaching efficacy, external locus of control, and self-esteem.

The Maslach Burnout Inventory was used to assess three facets of

burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and personal accomplishment.

An hypothesized model of burnout was tested in a LISREL analysis

with post hoc modifications indicating that role overload, work

pressure, classroom environment and self-esteem were predictors

of emotional exhaustion. Depersonalisation was significantly related

to emotional exhaustion, role conflict, selfesteem

and school environment. Teaching efficacy, self-esteem and depersonalisation

were predictors of personal accomplishment.

In 1974, Freudenberger introduced the term burnout to describe the

inability to function effectively in one's job as a consequence

of prolonged and extensive job related stress. Since that time,

incidences of, and research into stress and burnout have increased

with popular emphasis on employees in the human services sector

including social workers, nurses, teachers, lawyers, medical doctors

and police officers (Jackson, Schwab, & Schuler, 1986; Maslach

& Jackson, 1981). A common characteristic of these occupations

is that the nature of the work can be highly emotional. For teachers,

the potential for emotional stress is high since they work with

classes of up to 35 students for long periods of time. The intensely

relational nature of classrooms means that teachers are vulnerable

to emotionally draining and discouraging experiences (Maslach &

Leiter, 1999). Such experiences can lead to dysfunctional teacher

behaviour with obvious implications for the teacher’s well-being

and student learning.

This article reports the findings of a study of burnout in Queensland

private school teachers. Specifically, the study investigated the

influence of several hypothesized predictor variables. To provide

a contextual basis for the research, background information on theoretical

and empirical perspectives relating to this research is provided.

THEORETICAL AND EMPIRICAL PERSPECTIVES ON BURNOUT

According to Byrne (1991) and Maslach, Jackson, & Leiter (1996),

the burnout syndrome has three distinct but loosely coupled dimensions:

emotional exhaustion (feelings of being emotionally overextended

and exhausted with one's work), depersonalisation (the

development of negative and uncaring attitudes towards others),

and negative personal accomplishment (the loss of feelings of self-competence

and dissatisfaction with one's achievements). Maslach et al. have

developed and validated the Maslach Burnout Inventory

(MBI), an instrument that assesses these three dimensions. This

instrument has been used in burnout research across a wide range

of human environments.

Australian and overseas research has shown that high school teachers

exhibit high levels of stress when compared to other white collar

workers (Bransgrove, 1994). Otto (1986) showed that as many as one

third of Australian teachers reported being very or extremely stressed.

Teachers operating under high levels of stress for significant periods

of time can develop burnout characteristics including less sympathy

towards students, reduced tolerance of students, failure to prepare

lessons adequately and a lack of commitment to the teaching profession.

It follows that the study of teacher burnout is of great importance

to the productivity of teachers and subsequent student learning.

Early attempts to describe stress and burnout emphasized their personal

nature and, accordingly, blamed the individual teacher. This view

has been superseded by a more social view of burnout that recognizes

both background personality variables of the individual and

school characteristics as contributing to burnout in teachers. However,

most studies of burnout have focused largely on the investigation

of background variables like marital status, age, years of teaching

and gender as predictors of burnout (Anderson & Iwanicki, 1984;

Byrne, 1991, 1994; Malik, Mueller, & Meinke, 1991; Maslach &

Jackson, 1981). In fact, empirical studies involving psychosocial

environment dimensions of schools and classrooms as antecedents

to teacher burnout are rare.

According to Guglielmi and Tatrow (1998), serious conceptual problems

have confronted stress and burnout research. Two examples demonstrate

the divergent findings that can arise if variables are operationalized

in quite different ways. On the influence of student

misbehaviour on teacher stress, Hart, Wearing and Conn (1995) concluded

that ‘there is little point in trying to reduce teacher stress

by reducing student misbehaviour’ (p. 27). By contrast, Boyle,

Borg, Falzon and Baglioni (1995) reported that workload and student

misbehaviour accounted for the most variance in predicting teaching

stress. Hart et al. measured student misbehaviour with a single

self-report item that assessed the time that the teacher spent dealing

with student misbehaviour. It could be argued that such a simplistic

and naïve conceptualisation of student misbehaviour does not

in any way reflect the complex student misbehaviour issues that

teachers handle on a daily basis and which are not related to time.

Similarly, the measure of organizational climate employed by Hart

et al. is simplistic and does not reflect advances in school climate

research since the early 1980s (see, e.g. Fraser, 1994). It seems

clear that different researchers operationalize constructs in quite

different ways. Recent research involving burnout has investigated

links between teacher burnout and perceived self-efficacy in classroom

management (Brouwers & Tomic, 2000), compared stress and burnout

in rural and urban schools (Abel & Sewell, 1999), and studied

the sources of stress and burnout in Hong Kong teachers (Tang &

Yeung, 1999). Although research on learning environments and teacher

burnout have shown remarkable progress over the past 25 years, no

studies utilizing the latest approaches to research in these two

fields have been conducted. The recognition of school and classroom

environments as possible predictors of burnout is consistent with

Lens’s and Jesus’ (1999) psychosocial interpretation of

teacher stress and burnout and Maslach’s (1999) view that the

social environment is at the heart of both understanding the teacher

burnout phenomenon and ameliorating it.

Design of Present Study

The aims of the present study were to:

• validate scales to assess possible predictors of teacher

burnout (viz. school and classroom environment, work pressure, role

overload, role conflict, role ambiguity, teaching efficacy, locus

of control, self-esteem) and Maslach Burnout Inventory scales (viz.

emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and personal accomplishment),

and

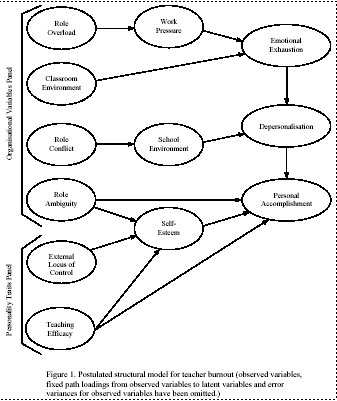

• investigate whether the postulated model of relationships

among the above predictors and Maslach Burnout Inventory scales

shown in Figure 1 fits the data through the use of structural equation

modelling.

Figure 1. Postulated structural model for teacher burnout (observed

variables,

fixed path loadings from observed variables to latent variables

and error

variances for observed variables have been omitted.)

As shown in Figure 1, both organizational and personality variables

predict burnout variables. It is noteworthy that this model was

based on Byrne’s (1994) research that has related a host of

variables with the three scales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory.

METHOD

Participants

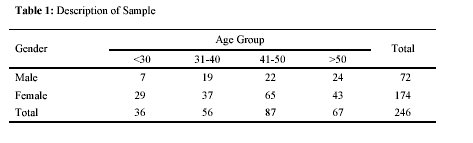

The sample employed in this study consisted of 246 teachers who

teach in private (i.e. nongovernment) schools in Queensland. Table

1 describes the sample which consisted of 99 primary, 103 secondary

and 44 teachers from combined primary and secondary schools. As

indicated earlier in this article, age and gender have been shown

to influence teacher burnout. While Table 1 describes the sample

in terms of gender and age group, these two variables are not the

focus of the present investigation.

Instrumentation

A test battery consisting of several instruments was administered

to each respondent. All instruments had been employed in previous

research in the United States but it was considered mandatory that

the psychometric properties of each scale be reported. Details of

the specific instruments which are described in Table 2 are as follows:

- Classroom environment. A 24-item

instrument which assesses teacher’s perceptions of their

classroom psychosocial environments was used. Items were taken

from four scales of a contemporary classroom environment instrument,

the What is Happening in this Classroom (Aldridge & Fraser,

2000; Fraser, 1998). These scales assessed Interactions, Cooperation,

Task Orientation, and Order and Organization in the classroom.

Because of the problematic nature of conducting structural equation

modelling with a large number of observed variables, a single

classroom environment score based on a linear combination of item

responses using

factor scores as coefficients was computed and used in subsequent

modelling. These factor scores were obtained from a confirmatory

factor analysis (CFA). All classroom environment items employed

a 5-point response format (viz. Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Not

Sure, Agree, and Strongly Agree).

- School environment. In an analogous

manner to the assessment of classroom environment, school-level

environment, was assessed with 36 items from an instrument employed

previously in school environment research (Dorman, Fraser, &

McRobbie, 1997).

These items were from six underlying scales (viz. mission consensus,

empowerment, student support, affiliation, professional interest,

and resource adequacy). As with classroom environment, a single

school environment score based on a linear combination of item

responses using factor scores from a CFA as coefficients was computed.

The response format for all school environment items was the same

as for classroom environment items.

- Role conflict, role ambiguity and role

overload. Three 5-item scales that have been validated

in previous research by Pettegrew and Wolf (1982) were used. These

scales have been successfully used by Byrne (1994) in teacher

burnout research in North America. All items employed a five point

response format (viz. Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Not Sure, Agree,

and Strongly Agree).

Table 2: Descriptive Information for Nine Predictor and Three Burnout

Scales

- Teaching efficacy. This 7-item

scale is from the Patterns of Adaptive Learning Survey(PALS) (Midgley

et al., 1997). Items employed the same five point response format

used for the above scales.

- Self-esteem. Seven

items from the adult form of Coopersmith’s (1981) Self-Esteem

Inventory were used. A five-point scoring format was used (viz.

Very Unlike Me, Unlike Me,Neither, Like Me, Very Like Me).

- External locus of control.

Byrne (1994) suggested the use of Rotter's Locus of Control scale

(MacDonald, 1974; Rotter, 1966) as a measure of locus of control

in burnout research. A modified 10-item form of Rotter's Locus

of Control scale was used. Items relating

to internal locus of control were reverse-scored so that scale

scores were an indication of the respondent's perceived level

of external locus of control. Items used a five point response

format: 1 (Strongly Disagree), 2 (Disagree), 3 (Not Sure), 4 (Agree),

and 5 (Strongly Agree).

- Burnout. A set of 19 items from

the latest version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory Form ES (MBI)

(Maslach et al., 1996) which has been developed especially for

educational institutions was used to provide a self-assessment

of each teacher's perceived burnout level. The original 22-item

MBI has three factor-analytically derived scales: emotional exhaustion,

depersonalisation and personal accomplishment. Whereas emotional

exhaustion and depersonalisation are positively related to burnout,

personal accomplishment is negatively related to burnout. A five-point

Likert response format ranging from Almost Never to Almost Always

was used to score each item.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

To investigate relationships among the above variables, structural

equation modelling (SEM) using LISREL 8.3 (Joreskog & Sorbom,1993)

was conducted. A weighted least squares (WLS) method with data from

polychoric correlation and asymptotic covariance matrices was

used in the analyses. The WLS method was preferred because item

data had five response categories, and polychoric correlations rather

than Pearson product.moment correlations were computed. In these

circumstances, Joreskog and Sorbom (1993) have argued that WLS is

the appropriate method of analysis.

There were two distinct components to the analyses conducted in

the present study. First, measurement models for each of the variables

were explored. While confirming the measurement of a particular

variable, each of these models provided factor scores to be used

in generating composite factor scores from items. Using theory described

by Holmes-Smith and Rowe (1994), these congeneric measurement models

maximized the reliability of composite and latent variables. This

was achieved by computing scale scores as linear combinations of

items with factor scores as item coefficients. According to Holmes-Smith

and Rowe, the composite score reliability (e.g. Cronbach alpha)

is maximized if the weights on each item (i.e. coefficients) are

corresponding factor scores rather than unity. Second, computed

composite variables were used subsequently in structural equation

modelling that examined relationships among latent variables. Munck

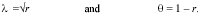

(1979) showed that path loadings  and error variances

and error variances  for observed variables can be fixed in structural equation modelling

and that, provided correlation matrices are analysed, they are related

to reliability (r) by the formulae

for observed variables can be fixed in structural equation modelling

and that, provided correlation matrices are analysed, they are related

to reliability (r) by the formulae

These formulae allow for paths from observed composite variables

to latent variables and error variances of observed composite variables

to be fixed. The advantage of this approach is that the number of

parameters to be estimated by LISREL is sharply reduced with consequent

improvement in model robustness.

Of the many indices available to report model fit, model comparison

and model parsimony in structural equation modelling, three indices

are reported in the present article: the Root Mean Square Error

of Approximation (RMSEA), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and the Parsimony

Normed Fit Index (PNFI). Whereas the RMSEA assesses model fit, the

TLI and PNFI assess model comparison and model parsimony respectively.

To interpret these indices, the following rules which are generally

accepted in the SEM literature as reflecting good models were adopted:

RMSEA should be below .05 with perfect fit indicated by an index

of zero, TLI should be above 0.90 with perfect fit indicated when

TLI = 1.00, and PFNI should be above 0.50 with indices above 0.70

unlikely even in a very sound fitting model. Further discussion

on indices and acceptable values is provided in Byrne (1998), Kelloway

(1998) and Schumacker and Lomax (1998). While the use of ¥ö2

tests to report goodness of fit of the model to the data is acknowledged

as problematic in SEM, it was used in the present study to report

improvements to the overall model fit as post hoc adjustments were

made.

Statistics reported in the present study included squared multiple

correlation coefficients (R2) for each structural equation and a

total coefficient of determination (Joreskog & Sorbom, 1989).

While R2 is a measure of the strength of a linear relationship,

the total coefficient of determination is the amount of variance

in the set of dependent variables explained by the set of independent

variables. In addition to overall fit statistics, it is important

to consider the strength and statistical significance of individual

parameters in the model. Each path was tested using a t-test (p

<.05).

|