|

If one studies Human Resources, one will notice that the field

seems to be missing architects – people who are able to connect

the dots and integrate the variety of HR subdisciplines and instruments

which are available. In many organizations the way HR is operating

today still resembles what people were doing around 1990, when the

word “Human Resources Management” started to replace the

term “Personnel Management”1. For instance, HR is the

only part of business which has “escaped” the business

process re-engineering movement of the 1990s. Even in the Internet

Age, one notices that after the e- learning and e-recruiting hype,

many companies are mainly still operating in the same ways as before

the Internet, and only using the Net as a way to deliver the same

messages as they delivered before.

Things can be different. For example, IBM centralized its global

recruiting, and manages most of it from one location in the U.K.

(and fired most of the local staff in HR). The result was that one

recruiter can now hire 90 persons a year versus a sector average

of 36 in 2000. Another company, BP, decided to outsource most of

its HR systems. In some companies, the demand for Return on Investment

(ROI) and productivity (less HR staff doing more work) are now getting

louder and louder.

This paper explains why and how to build an integral and more efficient

HR practice, starting

from an Integral Worldview in combination with state-of-the-art

technology.

The Integral Four Quadrant Approach

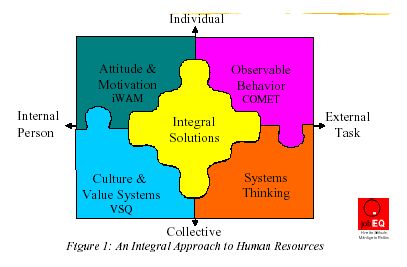

One of the major contributions of Ken Wilber, an contemporary American

philosopher, is his

approach to think at a level of abstraction at which various conflicting

approaches actually agree with one another. Then Wilber poses the

question: “What coherent system would in fact

incorporate the greatest number of these truths?”2 In this

paper, we have attempted something

similar for several approaches to HRM and psychology, grouping the

m in the four quadrants

Wilber typically used for organizing seemingly conflicting theories.

Indeed Wilber (1997) introduces the Integral Vision by pointing

out that some views of

reality start with objective, and often quantifiable observables.

This is called the external view (pictured as the quadrants at the

right side of figure 1). At the other side we have approaches that

start from introspection and interpretation, looking at consciousness

and at the direct experience that each of us has. These are called

the internal approaches (or the left side quadrants). Both sides

of the spectrum are then divided in individual approaches, where

one is looking at the parts (the Upper half of the drawing) and

collective approaches, where one is looking at the whole (the lower

half of the figure).3 In the sections that follow, we will discuss

the contribution of these four quadrants to an integral vision for

HRM.

Lower Right: Systems Thinking

Until the beginning of the 1990s, one could safely say that the

lower right quadrant was

often overlooked when implementing new programs in organizations.

But even more than 10

years after the hype of business process reengineering and the learning

organization, there is still something to learn for HRM. Symptoms

of a lack of a systemic view are for instance that

different HR programs do not take each other into account, leading

to incredible situations where the training and development department

in charge of training for the organization’s High-Potentials

organizes training without even being aware what the company’s

competence model for high-potentials is.

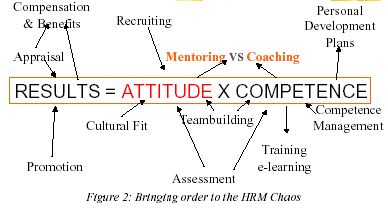

Connecting all the dots will greatly enhance the effectiveness of

an HRM effort. For

instance, if an organization decides to set up a mentoring or coaching

program, it’s recommended to brief mentors or coaches on the

competence models the company is using for the target audience of

these programs. Similarly, mentors and coaches should be helping

the person they are working with to integrate this mentoring and

coaching into their personal development plans, and hopefully the

organization is planning to let the persons put their new competencies

into practice, and this will be reflected at the next appraisal

or when the employees get promoted. The chart below, using jobEQ’s

formula for success, illustrates how all the dots need to be connected:

Upper Right: The Scientific View

Much of business is looked at from the external side, including

people. From this perspective, one is only interested in the observable

behavior of people. Much of what is called “competencies”

in HRM is based on this looking at what is observable. It is clear

that competence management is an important building block of an

integrated HR approach. This can happen in two ways: First, as Hamel

& Prahalad (1994) argue, an organization should determinewhich

are its core competencies related to its strategic position, thus

building competitive advantage. Secondly, an organization should

determine which are the important competencies for each position

in the organization, of course taking into account the core competencies.

The resulting competence models become the standard to be used for

many HR practices, such as assessment, recruitment, promotion, training,

coaching, and evaluating people. In other words, when competence

management is consistently applied throughout the organization,

it offers a way to connect the dots.

The mistake that is sometimes made by people designing competence

models is reducing

other elements such as the person’s motivational characteristics

to these competencies. In such a reductionistic model, being “proactive,”

“goal-oriented,” or “having attention for detail”

will be seen as competencies.

The limitations of this approach become clearly visible when one

sets loose statistical

factoring techniques on most competency-based questionnaires. In

fact, using these techniques, most of these questionnaires will

show very high correlations and tend to be reduced to one factor

only. This is clearly the result of a modeling error, since motivational

characteristics measured by a well-designed work attitude and motivation

questionnaire prove to have pretty low correlations between the

different attitude elements. In other words, using an upper right

method to predict upper left attitude characteristics is bound to

fail.

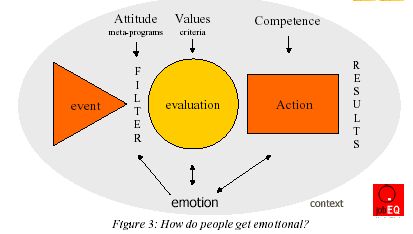

Upper Left: Individual Consideration

While the implementation of a coaching or mentoring program in an

organization includes a

systemic component, doing a particular coaching and mentoring intervention

starts from individual consideration. Instead of generalizing behavior,

our starting point is that each person may react differently when

confronted with the same event in the same context. Suppose for

instance that you get a compliment from a customer about your work.

Some people will feel happy about it. Others may doubt whether this

comment is really meant, and get mixed feelings, given that they

feel the compliment overstates what they have delivered. Others

might even react that the comment is not needed and might be wondering:

“What does this person want from me?”

The kind of response, both emotionally and in terms

of external behavior, will depend on

how this person filters reality. Is this the kind of person having

a strong external reference? In

that case, the likelihood of accepting the compliment and feeling

good because of it is greater.

Does a person have a strong internal reference? In that case, the

person is more likely to evaluate the compliments by their own criteria

and how they feel will depend more on their own evaluation.

How the person will respond will also depend on their criteria,

feelings and competences,

in this case for instance the question the person might be solving

is “What kind of response

should be given according to what they consider appropriate and

polite during these circumstances?”

In general, the last question can be generalized to: “In order

to reach the outcome I have in

mind, what works best in this context?” And if it doesn’t

work, the main recommendation we

have for the individual is to try something else. This way of looking

at the upper left quadrant

has been the focus of the book “7 Steps to Emotional Intelligence”

(2001).

Also when doing coaching, these are exactly the kind of questions

we will help the person

being coached to deal with. Here is a generic framework based on

the elements of figure 3:

Generic Individual Consideration Coaching format

Part 1: Take an issue you have been facing of

which you don’t like your emotional response or the action

you are taking.

Part 2: Exploring the issue and the response

a) Context: What, when, where did this happen?

b) Filters: What are you paying attention to in this situation?

c) Criteria: What kind of evaluation (judgment) are you making

about this situation? What are the

criteria that underlie this evaluation?

d) What kind of emotion does this bring along?

e) What kind of action have you taken or do you plan to take

because of this?

Part 3: Options for Change - choose any of these:

a) Changing the filters:

Which elements did you forget to bring into the picture? (People,

Things, Time, Money, Place,

Activities, Information, etc.) Who is responsible? What would

be another way to look at this?

b) Changing the emotion:

1) What is the message the emotion has for you?

What would be a more appropriate way to respond to that emotion?

Where is this emotion coming from (historically)? Is it relevant

(Is this message linked

to an emotional issue that needs to be addressed now)?

2) What would be another emotion to have that would serve you

better? How will that

emotion influence what you are attending, what you are thinking

and how you will be

responding?

c) Changing the criteria / beliefs:

What would be another way to evaluate this?

What stops you from seeing/taking this in another way?

What else is important in this context?

d) Changing the behavior:

How else could you respond? What else could you do?

e) Changing the context information:

How would you respond in a different context (or with another

person)?

What would you attend there? What criteria would you use? What

would you do differently?

Validation question: How would that make you feel? |

Note: Many of the change techniques covered

in parts 4 and 5 of the book “Mastering Mentoring and Coaching

with Emotional Intelligence (2004), and most NLP change methods

fit in this generic format. (e.g. reframing fits into changing the

filters and/or beliefs, much of the work with states fits under

“changing emotion”)

Lower Left: Culture

Apart from figuring out the competence model and taking into account

individual

characteristics such as work attitude and motivation, one also needs

to consider the

organizational culture. Approaches which will work in one organization

may fail in another one.

For instance, a study for the Dutch police force in 2003 showed

the unwanted side effects of

replacing the internal management training program by sending officers

to the Dutch business

schools where they enrolled in the standard MBA programs. Many of

the officers complained

that the managerial techniques learned in business school were difficult

to apply in the police

force. The main problem was that the cultural model underlying the

business training is not

compatible with the culture of the police force. In other words,

when examining the HR systems and tools of an organization, one

needs to have a way to map out the organizational culture.

Similar to what Ken Wilber did in his book “A Theory of Everything,”

we use the Value Systems model which was developed by Clare Graves4.

Based on extensive research, Graves proposed eight major levels

or waves of human

existence, of which two different ones dominate the culture of the

Dutch Police force and a

typical MBA program, respectively. In a business school, the main

level is “StriveDrive” (E-R) where people focus rationally

on their individual gains, analyzing and strategizing to prosper.

This type of culture is highly achievement-oriented and tends to

converge into materialistic

gains. In the Dutch police force, the main level is “HumanBond”

(F-S), where people put aside their personal gains for the good

of the community and feelings and caring supersede cold rationality.

At this level typical motivational systems from E-R, such as individual

bonuses stop working. Also, there is less respect for hierarchy

and officers are respected when they operate as team players.

Integral Thinking

In a nutshell, an integral HR Management aligns all HR tools with

the culture and the strategy of the organization, taking into account

the individual’s motivational characteristics.

The advantage is that HRM will become more efficie nt and effective,

contributing to the whole of the organization. This can be achieved

through examining which competencies, attitudes and value systems

are needed for various functions within the organization, and adapting

the HR systems and tools to these requirements.

References

Hamel, G & Prahalad, C.K., 1994, Competing for

the Future

Merlevede, P, Bridoux, D & Vandamme, R, 2001, 7 Steps to Emotional

Intelligence

Merlevede, P & Bridoux, D, 2004, Mastering Mentoring and Coaching

with Emotional Intelligence

Wilber, Ken, 1997, The Eye of Spirit

Wilber, Ken, 2000, A Theory of Everything

- For instance, the main HR organization in

the UK is called “Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development”

(CIPD). In the US, the “Society for Human Resource Management”

(SHRM) was founded in 1948 and was formerly called the “American

Society for Personnel Administration” (ASPA).

- Foreword “What’s the Meaning of

Integral” by Jack Crittenden in Ken Wilber (1997), “The

Eye of Spirit”.

- See for instance the introduction Ken Wilber

(1997), “The Eye of Spirit” (pages 4-29)

- An introduction of the Graves Value Systems

model, can be found in Wilber, K. (2000), A Theory of Everything.

A detailed explanation of the model can be found in: Clare W.

Graves (2002), Levels of Human Existence

|